I once knew a man. I will call him Alex. He lived about 15-20 minutes away from where I do now, but it’s in the direction I detour around if I have my children in the car with me. Instead of tree lined streets and quality schools, his neighborhood was riddled with gangs and shootings and hunger and homelessness.

Alex was a kind man. A very, very kind man. And he was smart. He had to have been. He managed to make his way in the world with a reading level lower than that of my six year old.

I met Alex when I was a literacy volunteer through a local ProLiteracy chapter. I had never really volunteered before. Of course I had done the service excursions that were presented to me in high school and in college, but really volunteering, going out and seeking a way I could make a difference, was something I had never ventured into. And it had really started weighing on me.

I was a college English teacher at the time, and so it made sense that any volunteering I would do would be somewhere in the realm of education. At the time I was teaching underprepared college students, and as I worked with them over the years, I had learned just how much of our situation in life relies on the manner in which we are able to communicate.

I would walk into a classroom, and I would see my students. I would hear them discuss difficulties they were having, and I knew without a shadow of a doubt that if they walked into a room or wrote a letter of complaint to get their issues taken care of that they would be glossed right over. Their dialects weren’t those prized in our society. Their writing didn’t bespeak high levels of education or influence. And as such, the amount of influence they had was very little.

It’s a sad fact of our society that those who have the most comfortable situations are those who are perceived to have the most power. While we convey power in many ways, the way we speak, write, and nonverbally communicate is one of the most obvious.

I worked with these students every day for years. Each semester would bring in a new batch of students with the same situations and the same difficulties. During those years of my life, that is where my heart resided.

And so when it came time to volunteer, I decided I wanted to take it one step further. These kids could read. They could write. They just didn’t do either with high levels of proficiency. But what about those who couldn’t even do that? What about those who couldn’t write a simple letter or fill out an application or read through a document? Those were the people I wanted to help.

And that led me to Alex.

He was a minority, and he had come from the South. He had a tough situation growing up, and it left him with very little formal education. This was through no fault of his own. In fact, he had such a low level of education because at a young age he had decided to devote his time and his life to taking care of those who needed it.

And now he was in his sixties, and he finally decided that it was time to take care of himself.

We worked together weekly, and he devoted himself to learning. But learning to read when you are 65 is much different than learning to read when you are 6. The brain just doesn’t acquire language in the same way. Each word was a struggle. And when he was finally able read a sentence of four or five words, he would beam at me with pride. He had absolutely no idea what he was reading, but he was so proud to be able to do it nonetheless. (This is when I learned that decoding and comprehension are very, very different things.)

We worked for awhile and then unfortunately he got very ill, and our relationship changed. Instead of working with him on reading, I was working with him on understanding his chemo protocols. I would go with him on doctor’s appointments because the doctors did not believe he was able to comprehend the decisions that were being placed before him. I visited him at the hospital the day after he had is colectomy.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t long after the surgery that we stopped meeting regularly. The treatments were making him too sick and too tired and he had to be really careful about going out in public with his compromised immune system.

I tried multiple times over the years to get into contact with him, but I haven’t had any luck. In my mind, he had given it his best shot, and he probably felt it was best to focus on other areas of his life. I constantly pray that he remembers those successes and that they allow him to have some confidence in his ability. Constantly I would remind him that education was different than intelligence. Just because he didn’t have the former didn’t mean he didn’t have the latter.

I share this story with you because I am working with Grammarly to help spread awareness about the importance of literacy in both individual lives and in society as a whole.

For Alex, literacy was a dream that he had held since childhood. To him, being able to read was a sign of success and intelligence and promise. In our culture, literacy is the doorway through which we must enter in order to fully benefit from the rights and privileges afforded to us as American citizens.

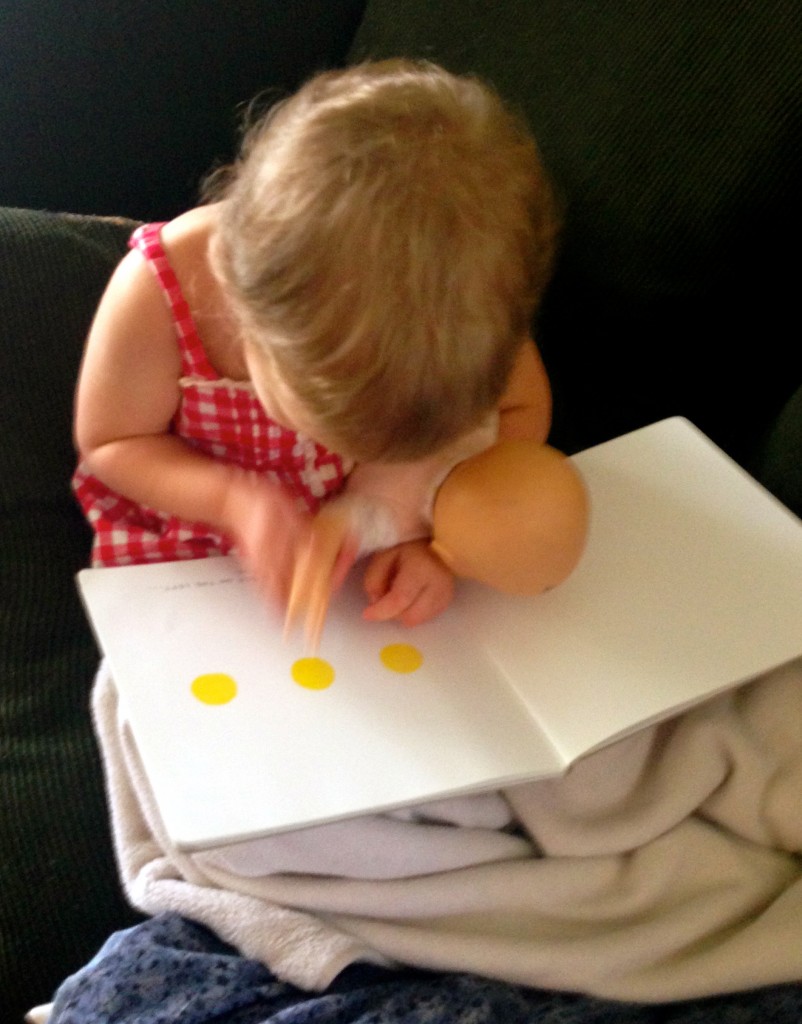

And yet we know that not all people have equal access to the development of literacy. Some children come from word rich environments. They are read to from the moment they are conceived and they go to good schools with ample resources. They then go home to parents who will encourage them and prompt them and believe in them.

And then there are children who go into kindergarten classrooms having never owned a book or possibly even held one. The scant books they have in their classrooms are older than their teachers. And their teachers are deeply passionate, but there is only so much they can do to overcome the hurdles presented to them — the violent neighborhoods, the culture of apathy, and possibly the illiterate parents.

These children are born into the same country, oftentimes the same city, and yet their lives will be so different. If disadvantaged children fail to gain adequate levels of literacy, it will define their lives.

According to Grammarly,

- “Low literacy affects more people that you think. About 22 percent of American adults have minimal literacy skills, which prevents them from effectively communicating. (National Center for Educational Statistics)

- Low literacy is correlated with chronic unemployment. 50 percent of the chronically unemployed are not functionally literate, which prevents them from maintaining jobs. (Ohio Literary Resource Center)

- Low literacy is correlated with imprisonment. 65 percent of prison inmates (or one million Americans) have low literacy. (Literacy Partners)

- Low literacy is correlated with poverty. 43 percent of Americans with low literacy are impoverished, lacking basic reading and writing skills to help them overcome their situations. (Literacy Partners)

- Low literacy affects the American economy. Experts estimate that low literacy costs the American economy $225 billion a year in lost productivity. Improved workplace literacy can increase employees’ efficiency, effectiveness, and productivity on the job. (Reach Higher, America)”

I read the newspaper, and I watch the news, and I look out my window, and so often things can seem so dismal. There is war and violence and poverty and crime, and there is very little, if nothing, I can do about most of it. But with literacy, there is something we can do.

There are many organizations out there that are looking for both volunteers and financial contributions. Some of them like ProLiteracy work with adults and families and others like Reading is Fundamental and Reach Out and Read work on getting books and literacy information into the hands of the most vulnerable of children and their caretakers.

Not all children have access to high quality education or libraries. Not all children have books. And not all children have access to adults who can or will or even know why they should read to them. And more often than not, these children will grow up to be the adults who need our help gaining those skills so that they can live the privileges that so many of us take for granted.

I know you are all busy, but if you have some time, take a look at some of these organizations and see if there is a way that you can help them. We invest so much in our own children. Hopefully every now and then we can help invest in the children that most of the world has forgotten.

Disclaimer: All opinions and ideas are entirely my own. In compensation for writing this post, Grammarly will donate money in my name to ProLiteracy. That’s pretty awesome of them, if you ask me. If you haven’t already, go check out the Grammarly Facebook page — it’s the perfect page for grammar nerds like yours truly.

You can follow Indisposable Mama by signing up for email notifications on the right or by becoming a fan of our Facebook page.